At Shark Group, we live in the space between an idea and its physical reality. It’s a thrilling place to be, but it’s also where countless brilliant product concepts meet their toughest critic: the real world of manufacturing.

You’ve likely seen it before. A designer envisions a product that is stunning, sleek, and revolutionary. It wins awards and gets rave reviews in focus groups. But when it lands on a factory floor, the response is a chorus of head-scratching and concerns. The angles are impossible to mold. The material choice is exotic and unproven. The assembly requires a robotic arm with the dexterity of a surgeon.

This is the classic tug-of-war between design and manufacturing. It’s not a battle of good versus evil, but rather a necessary dance between creativity and practicality. Mastering this dance isn’t just a nice-to-have skill; it’s the fundamental key to bringing successful, profitable, and high-quality products to market.

This is the art of Design for Manufacturability (DFM), and it’s the core philosophy that guides everything we do. In this guide, we’ll walk you through the essential principles of balancing design intent with manufacturing reality, ensuring your next product isn’t just a beautiful concept, but a commercial success.

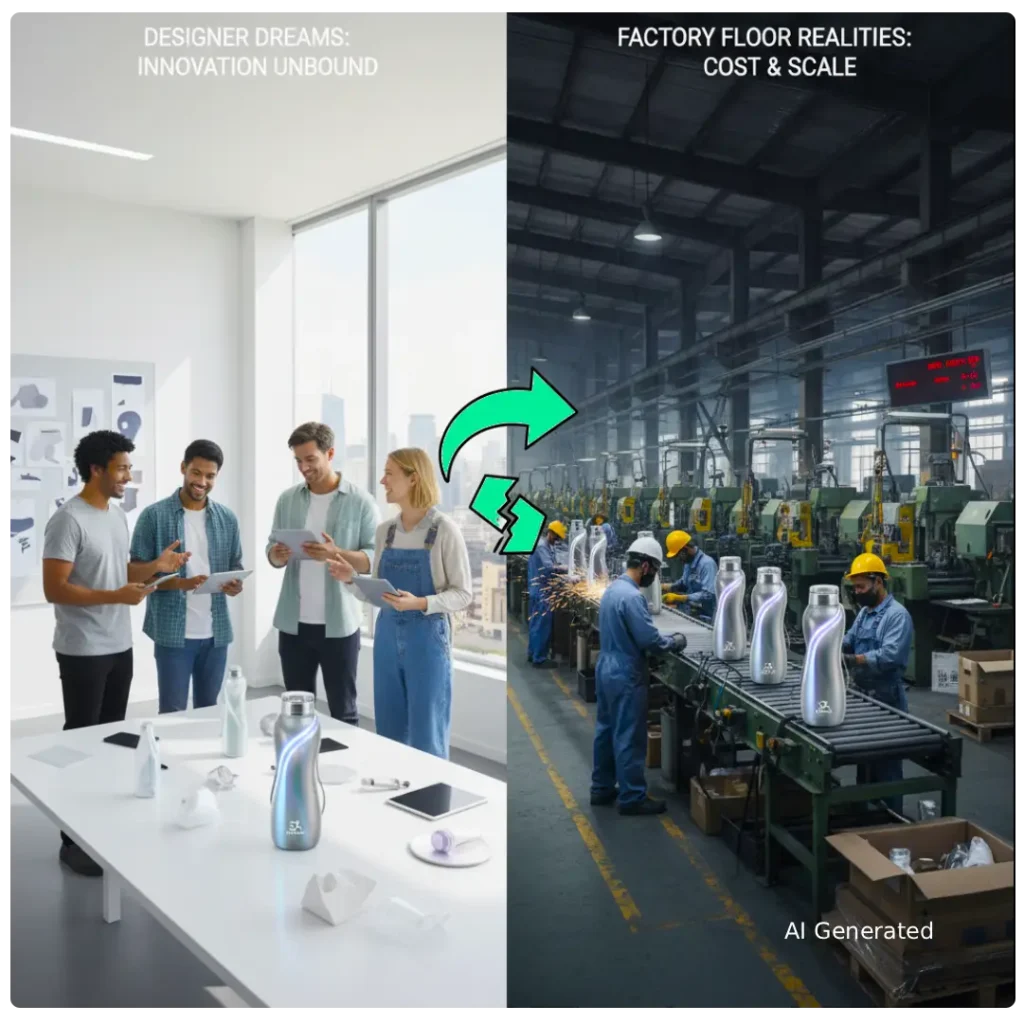

Why the Gap Exists: Designer Dreams vs. Factory Floor Realities

To bridge the gap, we first need to understand why it exists. Designers and manufacturing engineers often have different priorities, and both are valid.

The Designer’s Mindset:

- Goal: To create a product that is user-centric, aesthetically pleasing, and functionally innovative.

- Focus: User experience, form, brand identity, and solving a core problem in a novel way.

- The Blind Spot: Sometimes, the pursuit of a perfect user experience can lead to complex geometries, unique material feels, or intricate assemblies that are a nightmare to produce consistently and cost-effectively.

The Manufacturing Engineer’s Mindset:

- Goal: To produce thousands, or millions, of identical units with unwavering quality, minimal waste, and maximum efficiency.

- Focus: Tolerances, tooling design, production speed, cost per unit, and assembly line simplicity.

- The Blind Spot: An over-reliance on “how we’ve always done it” can sometimes stifle innovation and lead to suggestions that dilute a product’s unique design intent.

The magic happens when these two mindsets converge from day one. It’s not about one side “winning.” It’s about creating a shared language and a common goal: a well designed product that is also a well-made product.

The Pillars of a Successful Balance: Integrating DFM Early and Often

Achieving this balance rests on a few foundational pillars. By embedding these principles into your process, you avoid costly and time consuming redesigns down the road.

1. Foster Cross-Functional Collaboration from the Start

The single most important step is to break down the silos. At Shark Group, our design and engineering teams don’t work in sequence; they work in concert.

- Strategy: Involve manufacturing experts during the initial sketching and concept phase. Their early feedback on feasibility can gently steer a design in a more producible direction long before any hard tooling is commissioned.

- Benefit: This proactive approach catches potential issues when they are still easy and cheap to fix, on a digital screen, not with a $100,000 mold.

2. Embrace the Principles of Design for Manufacturability (DFM)

DFM is the systematic process of designing a product for ease of manufacturing. It’s the practical toolkit for achieving balance. Key DFM strategies include:

- Minimize Part Count: Ask yourself, “Can these two parts be combined into one?” Fewer parts mean less tooling, simpler assembly, lower inventory costs, and fewer potential failure points. A classic example is using living hinges or snap-fits instead of separate hinges and screws.

- Standardize Components: Where possible, use standard screws, bearings, and off-the-shelf electronics. Custom components are expensive and can lead to long lead times. Standard parts are proven, readily available, and cheap.

- Design for the Assembly Process: Think about how the product will be put together. Can it be assembled in a logical, top-down manner? Are there features like chamfers and guides to help align parts? Designing for easy assembly reduces labor time and the chance of human error.

- Choose Materials Wisely: Material selection is a triple constraint of cost, performance, and manufacturability. That beautiful, brushed titanium might be perfect for a luxury watch, but it’s overkill and prohibitively expensive for a children’s toy. Understand the material’s behavior in the chosen manufacturing process, how does it flow into a mold? How does it react to being stamped or bent?

3. Select the Right Manufacturing Process for Your Design

Your design and your manufacturing process are inextricably linked. You can’t design a part in a vacuum and then go shopping for a process to make it. Understanding the core processes is crucial.

Injection Molding:

- Best for: High-volume production of complex plastic parts.

- Design Balance Considerations:

- Draft Angles: All vertical walls must have a slight angle (draft) so the part can be ejected from the mold. A lack of draft is a common rookie mistake.

- Uniform Wall Thickness: This ensures the plastic fills the mold evenly and cools at the same rate, preventing defects like warping and sink marks.

- Appropriate Ribbing: Use ribs for strength instead of making entire walls thick, which saves material and reduces cycle time.

CNC Machining:

- Best for: Low to medium volumes, complex metal parts, and functional prototypes.

- Design Balance Considerations:

- Tool Access: Can a cutting tool physically reach all the surfaces it needs to machine? Avoid designing deep, narrow cavities with small openings.

- Internal Sharp Corners: Machining tools are round, so they create rounded internal corners. Designing a perfect, sharp internal corner is impossible and will drive up cost.

- Minimize Setups: Design parts that can be machined with as few re-orientations as possible.

3D Printing (Additive Manufacturing):

- Best for: Prototyping, highly complex geometries, and low-volume custom parts.

- Design Balance Considerations:

- Embrace Complexity: 3D printing excels at creating organic shapes, internal lattices, and consolidated assemblies that are impossible with other methods.

- Support Structure Removal: Understand that overhangs often require support structures that must be removed, which can leave marks and require post-processing.

- Anisotropic Properties: Parts may not be equally strong in all directions, which must be considered for load-bearing components.

Navigating Common Trade-Offs: The Heart of the Balancing Act

Even with the best collaboration, you will face trade-offs. How you navigate them defines the final product.

Trade-Off 1: Aesthetics vs. Cost

- The Scenario: The design team wants a seamless, unibody look with no visible parting lines. This requires a highly complex and expensive mold with actions (side-cores) and exquisite craftsmanship.

- The Balanced Solution: Can the parting line be cleverly hidden along a natural aesthetic edge or feature line? Sometimes, acknowledging the manufacturing process and designing with it, rather than against it, can create a beautiful and cost-effective detail. Communicating the significant cost savings of a simpler tool can allow the design team to explore other areas for aesthetic enhancement.

Trade-Off 2: Innovation vs. Timeline

- The Scenario: A groundbreaking new feature requires a novel material or an untested assembly technique.

- The Balanced Solution: Adopt a phased approach. Use rapid prototyping to validate the core function and user benefit of the innovation early. Run small-batch pilot production to de-risk the new process before committing to full-scale tooling. This mitigates timeline risk while still pursuing innovation.

Trade-Off 3: Perfect Function vs. “Good Enough”

- The Scenario: An internal component is designed to tolerances of ±0.01mm for peak performance, but the manufacturing team says ±0.05mm is more than adequate and will drastically reduce part cost and rejection rates.

- The Balanced Solution: This is where data rules. The design team must provide a clear rationale for the tighter tolerance. Is it critical for safety, performance, or user experience? If not, the manufacturing team’s “good enough” is often the smarter business decision. Challenge every specification to ensure it adds real value.

The Shark Group Approach: Making the Balance Our Default

For us, balancing design and manufacturing isn’t an afterthought, it’s the foundation of our product design and development process in the USA. We build this balance into our workflow through:

- Integrated Teams: Our industrial designers sit feet away from our mechanical engineers and manufacturing specialists. Conversations are constant and informal.

- Digital Prototyping & Simulation: Before a single physical part is made, we use advanced software to simulate how a design will behave during injection molding (warpage, fill analysis) or under stress (FEA). This virtual testing catches 95% of manufacturability issues.

- Strategic Prototyping: We use a mix of 3D printing for form and fit checks, and CNC-machined “looks-like, works-like” prototypes that use the intended production materials. This bridges the gap between a rough model and a final production part.

- Partnering with Factories: We have long-standing relationships with manufacturing partners, both domestically and overseas. We involve them in the review process early, treating them as experts, not just vendors.

Bottom Line

In the end, the art of balancing design and manufacturing isn’t about compromise; it’s about optimization. The most innovative product in the world is a failure if it can’t be made reliably and affordably. Conversely, the easiest product to manufacture is often a generic, me-too commodity that no one wants to buy.

The sweet spot, the true masterpiece, is the product that feels inevitable. Its form and function are so perfectly harmonized with how it’s made that it seems there was no other way it could have been. Achieving this requires empathy, not just expertise: designers who understand the poetry of a production line, and engineers who appreciate the power of a beautiful curve.

At Shark Group, we believe this balance is where great ideas become great products. It’s the disciplined, collaborative, and deeply rewarding art of turning imagination into reality.